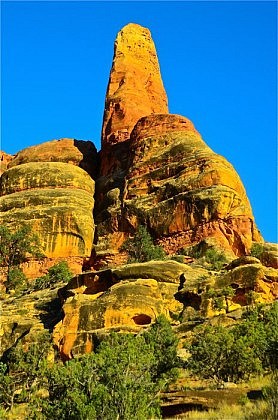

A funny thing happened on the way to wolf recovery. While leading our guided Yellowstone backpacking trips, by the late 1990’s I began to notice that old dying aspen stands were beginning to sprout vigorous new saplings. Now, 24 years after the 1995 wolf re-introduction, these important deciduous habitats are thriving once again. Willow stands also quickly began to come back from near oblivion. With this increase in food and building materials, beaver populations rebounded, and their dams created or re-created wetlands. Biodiversity, especially among birds, insects and amphibians rebounded.

And although elk populations remain healthy throughout the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem (GYE), their numbers dropped — modestly in some areas and substantially along Yellowstone’s northern boundary. The reduction in elk numbers began shortly after wolf re-introduction in 1995.

It turns out, then, that at least in many habitats, the warming climate was not the culprit for aspen and willow decline. It is much more likely that the primary cause was a lack of large carnivores. As large carnivores made a comeback, elk populations declined. And since elk eat young aspen and willow shoots, fewer elk meant less browsing, and less browsing has allowed aspen and willows to reproduce. But it isn’t just wolves that are responsible for fewer elk and thus more aspen. Concurrent with wolf restoration has been the gradual recovery of mountain lion and grizzly populations throughout the GYE, species that also prey on Yellowstone’s productive elk herds. So there you have it. Although Yellowstone’s climate is warming and drying, the major reason for elk decline and the resulting increase in deciduous vegetation is much more likely to be the rebounding populations of all three large carnivores, not just wolves. Yet this conclusion does not complete this picture.

Note that I qualified the earlier statement with terms such as “major” and “more likely”. Carnivore rebound is probably not the only cause for aspen and willow resurgence. For one thing, big wildfires in 1988 and in various years since, have also promoted aspen growth, both by providing fertile mineral soil seed beds, and also by creating “blow-down jungles” where elk don’t dare to venture in the carnivore-rich landscape. It is tough to escape an ambush when you are impeded by piles of dead-fall. Moreover, while the restoration of big carnivores has helped aspen and willow growth, aspen and willow have not rebounded across the board throughout the region. In fact, there are areas in the GYE where climate change has slowed down or prevented this response. Some areas are now simply too dry for aspen or willow, though they supported these species before. In addition, note that grizzlies and mountain lions are also part of the equation. In other words, this so-called “trophic cascade” (a situation in which addition or subtraction of one or more ecosystem components has often unforeseen ecosystem consequences which may either promote or suppress biological diversity). In other words, nothing is simple in nature, and most “effects” have more than one cause. And what we think we know today may turn out to be something entirely different tomorrow.