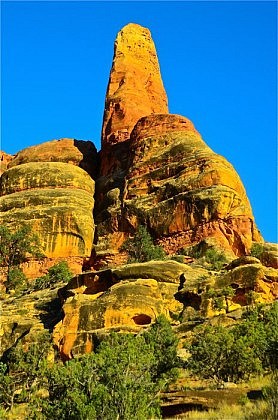

By the time the U.S. stock market crashed in 1929, the native gray wolf (northern Rocky Mountain subspecies, Canis lupus irremotus) had been essentially exterminated throughout the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem (GYE). The extermination was intentional, primarily to benefit cattle and sheep ranchers who had no use for predators that enjoy an occasional meal of beef or mutton. But extermination was also supported by many hunters, who simply didn’t want to share “their” elk and deer with wolves and other large carnivores (mountain lions and grizzlies were in trouble by the 1970’s). So, guided Yellowstone backpacking treks became a tamer experience, one that took in beautiful scenery in a semi-wild landscape that was missing its dynamic essence of the ancient drama of big predators and their prey.

Then, beginning in 1995, after being absent for three quarters of a century, wolves were re-introduced directly into Yellowstone’s Lamar River Valley. During their absence, the GYE’s only native upland deciduous tree, quaking aspen, was slowly dying out, disappearing from many of its previous habitats. Conjecture suggested that aspens were disappearing due to the well-documented warming and drying climate. But in this case, this simple cause and effect assumption turned out to be wrong. More on this shortly. Anyway, the wolf reintroduction program was wildly successful, taking just a few years for wolves to spread throughout the GYE. This success should have surprised no one, since the Yellowstone Ecosystem is known around the globe for providing rich wildland habitat for huge herds of hoofed mammals, plus many smaller critters as well. In other words, big chunks of wild habitat plus plenty to eat equals an ideal situation for growing wolves — and other large carnivores, too.

As quaking aspen stands gradually died out with minimal replacement, so did willows, another deciduous species that usually forms shrubby thickets primarily in riparian habitats. Willow and aspen are beaver food, and as these members of the willow family declined, so did beaver populations. As beavers declined, so did wetlands — and various birds and amphibians dependent upon them. Other birds and mammals that prefer leafy deciduous species such as aspen also declined. As we shall see, though, mother nature once again threw us a curve-ball, showing us that obvious conclusions are often erroneous conclusions. Stay tuned to the rest of this story in my next installment.