Our nation’s first official Wilderness was the Gila Wilderness, protected administratively by the Forest Service in 1924 at the urging of legendary conservationist Aldo Leopold. The Big Wild Adventures guided New Mexico hiking tour in the Gila Wilderness is offered every other year. So begin to plan now for 2019!

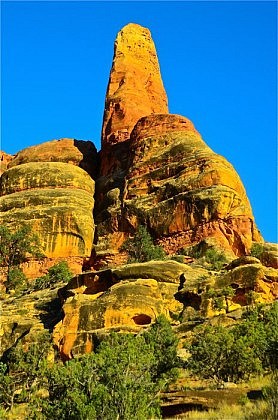

Our 2017 adventure was led by Big Wild co-owner Howie, with an assist from Big Wild guide Jesse Ford. And it had an international flavor, with Brits Ollie and Harriet plus Michael, a long time Big Wild client from Taiwan. Lisa and Ann rounded out the group. The Gila is the largest forested Wilderness in southwestern North America, a high elevation volcanic plateau with scattered mountain ranges and spectacular river canyons. If that sounds a lot like the terrain in Yellowstone, well, that’s because the geologic similarities with our Yellowstone backpacking trips are real! And despite the southerly latitude, this New Mexico backpacking trip is high above the surrounding desert in a land of towering conifer trees, most notably ponderosa pines. It is a spectacular open grassy forest of huge, widely spaced majestic ponderosas and we walked through it for the vast majority of the trips’ mileage!

The usual spring weather in the Gila is dry, and 2017 was typical. Though there was plenty of water in the streams, we had seven nearly cloudless days with no rain. I slept under the stars all week and never set up my tent! As is also typical, day/night temperature differences in the thin dry air were huge: at least a couple of days saw temperatures rise from the mid-20’s at dawn to the mid 80’s under an intense afternoon southwestern sun! We covered about 45 miles, mostly on good trails and made it to the heart of the Wilderness, as far from a road as you can get in the Gila without beginning to come out the other side. It was big and wild and everyone in this eclectic international backpacking group was a great backpacking companion. We look forward to many more adventures with these great folks who joined us for our 2017 New Mexico backpack trip!