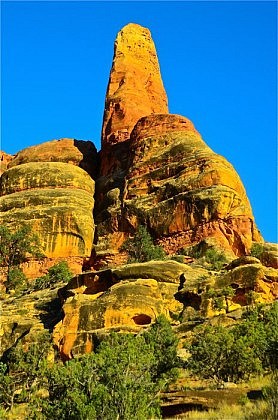

Thunderstorms are a part of the wilderness experience in most high mountain regions during the warmer months of the year. This is certainly true in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem (GYE), which includes Yellowstone National Park and surrounding mountain ranges such as the Absarokas, Beartooths, Wind Rivers, Tetons, Gallatins and Gros Ventres.

A couple of geographic/meteorological factors are responsible for most thunderstorms in this unique highland region. First, the GYE is a very expansive highland of alpine mountains and high plateaus, rising well above the much lower grasslands, croplands and sagebrush steppes of the surrounding terrain. The expansive upland forces moist air to rise and condense into clouds, regardless of the direction from which the moist air arrives. Moist Pacific fronts and air masses and moist subtropical air flow can each produce sudden, sometimes violent thunderstorms when the moist unstable air is forced upward by the terrain. There’s an old saying that “mountains make their own weather”, and although highlands do so in many ways, orographic lifting (air masses forced to rise over high topography) in conjunction with convective daytime heating is probably the most typical example of thunderstorm formation in the mountains. It also facilitates cloud formation and precipitation during other seasons in addition to summer thunderstorms, so in general, the high country climate is cooler and wetter than that of the surrounding lowlands.

In the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, there’s another important factor in thunderstorm formation. Most summers, a true monsoon develops over Mexico and the American Southwest, bringing moist tropical air from the Gulf of California, the Gulf of Mexico and the subtropical Pacific into the region. Typically, this moist flow brings daily scattered but intense thunderstorms during July, August and early September to Arizona, New Mexico and the mountains of Colorado. But occasionally, the monsoon continues north into western Wyoming and southern Montana. It often drifts far enough to the east to miss most of Idaho and far western Montana, resulting in drier summer for the Bitterroot Range and neighboring areas. When the monsoon does drift to the north and east, the orographic effect of the Greater Yellowstone highland facilitates cloud formation, and boom! Before you know it the temperature has dropped 20 degrees and you are cowering in the trees, trying to stay warm, dry and non-electrical! Yes, those picturesque puffy white morning cumulus clouds in the deep blue sky sure look innocuous. But they can grow into massive thunderheads before you can say “head for cover!” In the next installment, we’ll discuss some signs of thunderous danger and then we’ll look at some of the best ways to avoid getting zapped by lightening while backpacking in Yellowstone and adjacent mountain ranges. Stay tuned!