In the previous installment, I discussed the geographical quirk that the wildest areas of Montana are all border areas, shared with Canada, Idaho and Wyoming. The wild Northern Continental Divide Ecosystem along the Canadian border includes the 2.4 million acre Bob Marshall Wilderness complex, which is actually one unbroken chunk of roadless, undeveloped wild country. Maps depict three different Wilderness Units here (The Bob Marshall, Scapegoat and Great Bear), but these three Wildernesses actually constitute one unbroken wild area, divided by bureaucrats and politicians along pre-existing national forest and ranger district boundaries.

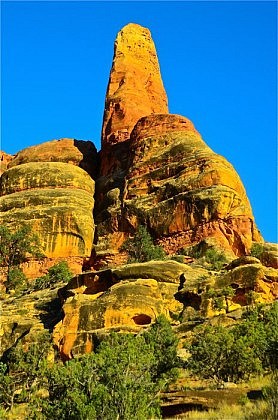

“The Bob”, as this wild-land is affectionately known, was named for wilderness visionary Robert Marshall, and includes a lot of unprotected roadless country hugging the outer boundaries of the “three” Wilderness areas. With a moisture gradient running from wet forests on the west side of The Bob to foothills prairie along the eastern “Rocky Mountain Front”, the Bob Marshall is a huge diverse chunk of wilderness, a wilder and less-visited chunk of the Big Wild than its more famous neighbor to the north. Our trips in the Bob Marshall Wilderness are primarily along the east side of the continental Divide, where the Rocky Mountains rise in dramatic fashion above the short-grass prairies just to the east. This is the most dramatic area of the greater Bob Marshall Complex.

Our guided and outfitted Bob Marshall Wilderness backpack trips begin and end in Great Falls, Montana. Rugged limestone peaks, dense forests, aspen groves, beautiful meadows, waterfalls, snowfields and more grace this “fairly strenuous” guided backpacking trip. There’s plenty of native wildlife, too, and last year we had a lone gray wolf visit our camp on the second morning of the trip. We were wolf-watching before our very first cup of coffee!